oh yeah. I know all of that, and have played (on drums and also bass) and taught much of those styles of music over the past 30 years as a middle/high school band director

agreed, but that doesn't make it

more correct. It just means that it was the popular choice of the day/time. Just like an artist being popular does not automatically make them a good musician...it makes them lucky, and possibly business smart...there are tons of popular musicians who are not good musicians

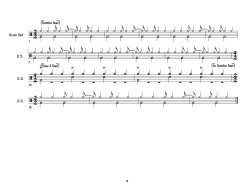

except that 100% of the time, I count my train beats as 16th notes...and that is b/c I almost always put my bass drum as 1 and 3 in my head, and snare as 2 and 4. I base all of my drum set division on that concept. And the audience never knows, which I think is the most important thing. If the train beat is moving the audience, it doesn't matter whether it is in 2 or 4

and I am not refuting anything you are saying, other than it has to be strictly written out in 2/2.

as a small history, I cut my teeth reading music in marching band stuff, and most of what I was reading was 16th note stuff in 4/4. That is probably why it is so ingrained in me to count that way. Over the years, when I get a song in 2/2, I have trained my self to convert it to 2/4 right away.

Again, it is just a personal thing...like my disdain for social media, and my refusal to participate in it in any way. I will never win the "war on cut time"...it is me just being a bit of a baby really